Bernstein-Vazirani Algorithm

The Bernstein-Vazirani (BV) algorithm [1], named after Ethan Bernstein and Umesh Vazirani, is a basic quantum algorithm. It gives a linear speedup compared to its classical counterpart, in the oracle complexity setting.

The algorithm treats the following problem:

- Input: A Boolean function \(f: \{0,1\}^n \rightarrow \{0,1\}\) defined as

where the \(\cdot\) refers to a bitwise dot operation, and \(a\) is a binary string of length \(n\).

- Output: Returns the secret string \(a\) with minimum inquiries of the function.

Comments:

-

This problem is a special case of the hidden-shift problem, where the goal is to find a secret string satisfing \(f(x)=f(x\oplus a)\), with \(\oplus\) indicating bitwise addition.

-

The problem is a restricted version of the Deutsch-Jozsa algorithm. In particular, the functional quantum circuit is identical for both problems.

Problem hardness: Classically, the minimum inquiries of the function \(f\) for determining the secret string is \(n\): \(f\) is called with these strings:

which reveals the secret string, one bit at a time. The BV algorithm finds the secret string using one function call (oracle inquiry), thereby providing a linear speedup with respect to the classical solution.

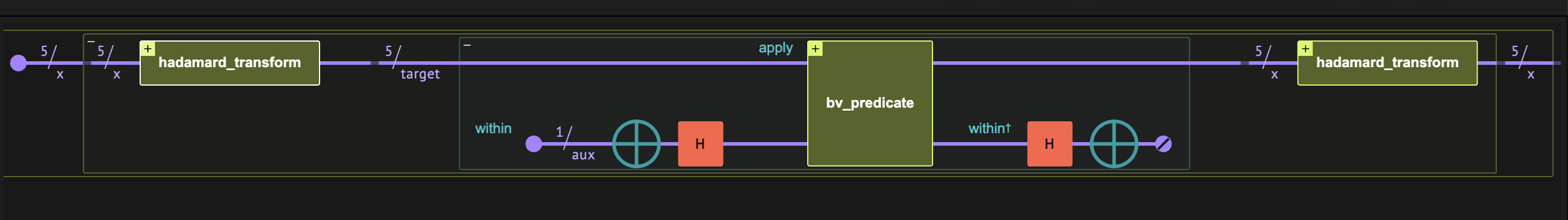

Figure 1. The Bernstein-Vazirani algorithm comprises three quantum blocks. The main part of the algorithm is the implementation of the Bernstein-Vazirani predicate \(f(x)\equiv (x\cdot a) \mod 2\).

How to Build the Algorithm with Classiq

The BV algorithm contains three function blocks: an oracle for the predicate \(f\), "sandwiched" between two Hadamard transforms. The resulting state corresponds to the secret string. The full mathematical derivation is at the end of this notebook.

Implementing the BV Predicate

A simple quantum implementation of the binary function \(f(x)\) applies a series of controlled-X operations: starting with the state \(|f\rangle=|0\rangle\), we apply an X gate, controlled on the \(|x_i\rangle\) state, for all \(i\) such that \(a_i=1\):

from classiq import *

from classiq.qmod.symbolic import floor

@qfunc

def bv_predicate(a: CInt, x: Const[QArray], res: Permutable[QBit]):

repeat(

x.len,

lambda i: if_(floor(a / 2**i) % 2 == 1, lambda: CX(x[i], res)),

)

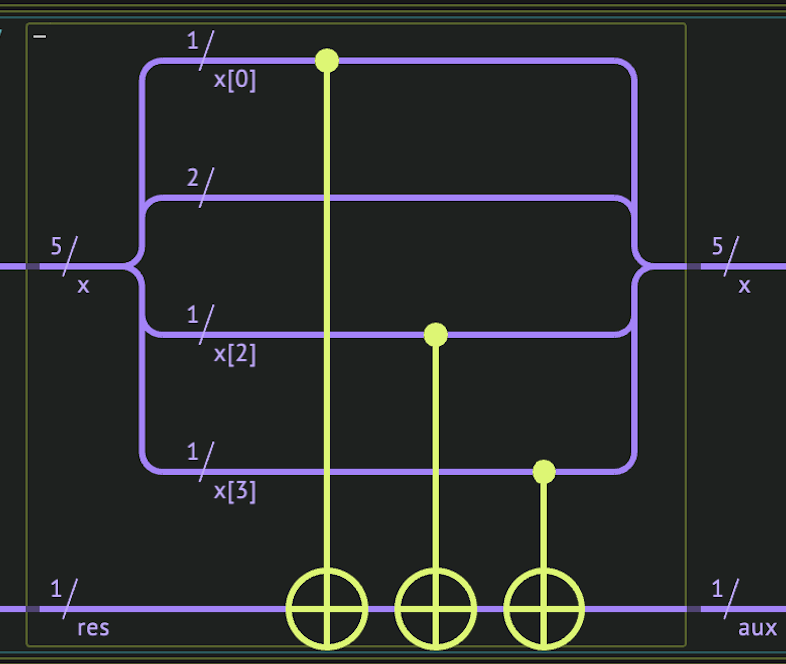

Figure 2 shows an example of such implementation, for \(a=01101\) and \(n=5\).

Figure 2. The Bernstein-Vazirani predicate \(f(x)\) for a secret string \(a=01101\), on \(n\) qubits. The quantum variable \(x\) is stored on the five upper qubits and the resulting value of \(f\) is on the lowermost qubit.

Implementing the BV Quantum Function

The quantum part of the BV algorithm is essentially identical to the deutsch_jozsa function in the Deutsch-Jozsa notebook. However, in contrast to the latter, the predicate function implementation is fixed, depending solely on the secret string \(a\). Hereafter, we refer to the secret string as a secret integer, defined as an integer argument for the bv_function:

@qfunc

def bv_function(a: CInt, x: QArray):

aux = QBit()

within_apply(

lambda: hadamard_transform(x),

lambda: within_apply(

lambda: (allocate(aux), X(aux), H(aux)), lambda: bv_predicate(a, x, aux)

),

)

An Example on Five Qubits

We construct a model for a specific example, setting the secret integer to \(a=13\) and \(n=5\).

We can essentially set the number of shots to 1. This is because that under the assumption of noiseless execution, the resulting state is just the secret integer (see the last Eq. (1) below). In particular, the idea of using solely one shot demonstrated algorithmic speedup in Ref. [2], where the authors considered a modified version of the BV algorithm in which the secret integer changes after every inquiry.

In this example, we take num_shots=1000 to highlight the fact that the resulting state is purely the secret string.

import numpy as np

from classiq.execution import ExecutionPreferences

SECRET_INT = 13

STRING_LENGTH = 5

NUM_SHOTS = 1000

assert (

np.floor(np.log2(SECRET_INT) + 1) <= STRING_LENGTH

), "The STRING_LENGTH cannot be smaller than secret string length"

@qfunc

def main(x: Output[QNum[STRING_LENGTH]]):

allocate(x)

bv_function(SECRET_INT, x)

qmod = create_model(

main,

execution_preferences=ExecutionPreferences(num_shots=NUM_SHOTS),

out_file="bernstein_vazirani_example",

)

qprog = synthesize(qmod)

We can now visualize the circuit:

show(qprog)

Quantum program link: https://platform.classiq.io/circuit/2yrQrjHk0Y8dINWarXC3rtNRvm5

We execute and extract the result:

result = execute(qprog).result_value()

secret_integer_q = result.parsed_counts[0].state["x"]

print("The secret integer is:", secret_integer_q)

print(

"The probability for measuring the secret integer is:",

result.parsed_counts[0].shots / NUM_SHOTS,

)

assert int(secret_integer_q) == SECRET_INT

The secret integer is: 13

The probability for measuring the secret integer is: 1.0

Technical Notes

Here is a brief summary of the linear algebra behind the Bernstein-Vazirani algorithm. The first Hadamard transformation generates an equal superposition over all the standard basis elements:

The oracle gets the Boolean Bernstein-Vazirani predicate and adds an \(e^{\pi i}=-1\) phase to all states for which the function returns true:

Finally, application of the Hadamard transform, which can be written as \(H^{\otimes n}\equiv \frac{1}{2^{n/2}}\sum^{2^n-1}_{k,l=0}(-1)^{k\cdot l} |k\rangle \langle l|\), gives

The final expression represents a superposition over all basis states \(|k\rangle\); however, we can verify that the amplitude of the state \(|k\rangle=|a\rangle\) is simply one, as \(a\oplus a =0\):

Therefore, the final state is the secret string.

References

[1]: Bernstein–Vazirani (Wikipedia)

[2]: Pokharel B., and Daniel A. L. "Demonstration of algorithmic quantum speedup." Physical Review Letters 130, 210602 (2023)